Guest Post - Q&A

With Caroline Angus

Today we are thrilled to welcome Caroline Angus to The Tudor Notebook to discuss her latest book and all things Thomas Cromwell.

Caroline gives us incredible insight into the Tudor court Cromwell knew so well, so grab a drink and some snacks, get comfortable and keep reading.

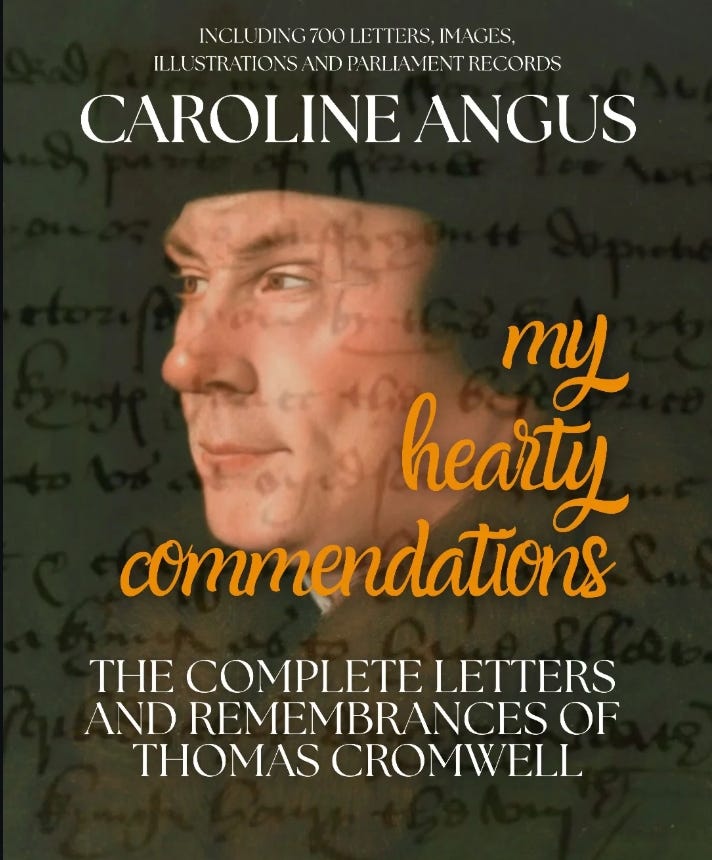

Hi Caroline, thank you so much for taking the time to answer a few questions about your writing today. Caroline is an expert on Thomas Cromwell and her latest book is called “My Hearty Commendations: The Transcribed Letters and remembrances of Thomas Cromwell” - which is a new and updated edition of the original published in 2020. It has over 700 entries, 150 of which are new to this edition. I’ve read the book, and think it is an invaluable resource to anyone studying Tudor England.

What first drew you to Thomas Cromwell as a research subject?

I didn’t come across Thomas Cromwell until 2008, when I was home in New Zealand with my mother who was suffering cancer, and she was watching The Tudors series, which instantly intrigued me because local Sam Neill was in it as Wolsey. Everyone of course knows Henry VIII and I have always been a fan of Katharine of Aragon, the true queen, but I knew nothing of Cromwell until my mother pointed him out on screen as the sneaky, interesting character. The tv series, while inaccurate, is an excellent gateway for many people, and Cromwell’s death is portrayed very well in terms of accuracy, and beautifully played. But I was still deep in my research about Spain at the time and it wasn’t until 2015 that I was looking for a break in my Spanish studies, and stumbled upon Thomas Cromwell again. I immediately felt that a character like him, who was born with nothing and rose up without any loyalties and predictable back story could be a source I could really work with in fiction. I ended up writing three books on him in three years to fit his incredible life as I chose to see it, an emotional private life around the public life that we know of him. I studied on the job; I researched him as I wrote the story of him and his fictional secretary Nicola Frescobaldi, the son of Cromwell’s real-life Italian patron. Once I was finished with the series, I left with thousands of pages of research on his work, and I started 2020 thinking it could be a fun new project to complete a book on the letters, naturally not seeing what the world was about to throw at us all only weeks later. There is a book of Cromwell’s letters by Roger Meriman published in 1902, but it is missing so much of what we now know belongs to Cromwell, plus what I found among other figures’ papers while researching, and I wanted to collate everything.

Your book contains letters and remembrances that cover every aspect of Cromwell’s life. What was the greatest challenge you faced when transcribing his letters?

The biggest problem in covering Cromwell is that he is hiding in archives. You need to read where he isn’t mentioned rather than where he is to see what is going on. When Cromwell died in 1540, two men, Henry Polstead, one of Cromwell’s legal secretaries, and Thomas Ryther, one of the overseers at Austin Friars, were left in charge of the property to catalogue its inventory, and most of Cromwell’s work in his own writing was ‘lost’ and destroyed. The most important parts of Cromwell’s political life are missing. The parliaments that he ran in the 1530s all have damaged records or have no records left at all (whoever decided to destroy the Reformation parliaments did miss the 1534 House of Lords notes, but that’s all that survived). There has been a very orchestrated attempt to eliminate what happened in the 1530s, and while I suspect much of this was done to protect Cromwell and his reputation, even before his death, time has also played a major role, with many surviving papers damaged by water and fire. Cromwell beheaded a queen and created the Anglican Church, and yet he was forgotten by historians and archivists until the mid-twentieth century as he was overshadowed by the dissolution of the monasteries. Another issue is that correspondence between Cromwell and Thomas Cranmer were also destroyed. Cranmer had his secretary Ralph Morice keep a ledger of all letters that came in, and a separate ledger only recording letters from Cromwell. The ledger only lasted a few weeks before it was abandoned, and their correspondence went unrecorded, leaving so many gaps in their work. The men had few allies besides each other at times, and the loss of their letters leaves many questions.

I loved the wealth of detail contained within his letters, and the way in which they breathe life into forgotten people, if only for a moment. For example Lady Alice Clere who Cromwell assisted when her family was in financial difficulties, for a moment leaps from the page, worried and hoping for help. (Letter 20 in the book LP iv. No. 3741) Do you have a favourite letter of Cromwell’s?

The first letter that always comes to mind is a letter Cromwell wrote to Nicholas Shaxton, Bishop of Salisbury in March 1538. Most of the long-form letters that survive are quiet formal, while this one is different. Shaxton was an early reformer that escaped Thomas More’s torture and was brought to court by Anne Boleyn, before being moved into Cranmer’s and then Cromwell’s circles and made a bishop in 1534. Since then, there were endless complaints made about Shaxton and his preaching and living as the Reformation continued. He had failed to sufficiently interrogate ‘heretics’ in his area and that is when Cromwell stepped in personally to deal with issues around Salisbury, injuring Shaxton’s pride. The two traded letters on the subject, with Shaxton claiming his letters were covered in salty tears Cromwell because thought badly of him without cause. Shaxton’s letters survive, but only one of the letters to Shaxton from Cromwell’s survives, and it is impressive, as it shows a man clearly angry with dealing with trifling (in comparison to his workload) issues, but still prepared to give Shaxton another chance. The men had traded barbs and Shaxton had accused Cromwell of overreaching in his powers (impossible to do as Vicegerent of England), not helping or writing to Shaxton as often as he needed, and Cromwell was not prepared to let the accusations sit unanswered. Among the many great lines Cromwell delivers, he says:

‘My lord, I pray you, while I am your friend, take me to be so, for if I were not, or if I knew any cause why I ought not, as I would not be afraid to show you what had alienated my mind from you, so you should well perceive that my displeasure should last no longer than there were cause... I may err in my doings for want of knowledge, I willingly bear no misdoers. I willingly hurt none whom honesty and the king’s law do not refuse. Undo not you yourself, I intend nothing less than to work you any displeasure. If hitherto, I have showed you any pleasure, I am glad of it, I showed it to your qualities and not to you. If they tarry with you, my goodwill cannot depart from you, except to prayer be heard that is my heart be torn.’

Another is an excellent letter from September 1537 to Michael Throckmorton, servant of Cardinal Reginald Pole. Cromwell had long been friendly with the Throckmorton family, but Michael Throckmorton had been in Europe with Pole for some time, and was one of the chief men who funneled gossip about Cromwell to Pole, and copied Cromwell’s letters sent to Pole and others, thus sharing private correspondence. Pole had been sending letters to England through Throckmorton, suggesting he meet with Cromwell in the Low Countries, to discuss religion and King Henry, an obvious trap nobody in England considered a serious option. This letter came a year before Cromwell was tasked with destroying the Pole family, and Cromwell wrote to Throckmorton, in a rare letter than shows Cromwell’s anger:

‘But I now remember myself too late. I might better have judged that so dishonest a master could have but even such a servant as you are. No, no, loyalty and treason dwell seldom together. There can be no faithful subject who so long abides the sight of so heinous a traitor to his prince... No, you and your master have both well declared how little fear of God rests in you, which was led by vain promise of promotion, thus against the king’s laws, and you work treason towards your natural prince and country, to serve an enemy of God, an enemy of all honesty, an enemy of right religion, a defender of iniquity, of pride, a merchant and occupier of all deceit, and of twenty things that no honest men can well touch, much less utter and put forth... You have blurred my eyes, and your credit shall nevermore serve you so far to deceive me the second time. I take you as you are and do think it much light for you to forge letters, which by words, not long sought for, thus have deceived me... . If you continue in your malice, and perverse blindness; doubt you not, but your ends shall be as of all traitors for the most part is. I have done what I may, to save you. I must I think do what I can to see you condignly punished. God send you both to fare as you deserve, that is either shortly to come to your allegiance or else to a shameful death.’

What do you think was Cromwell’s greatest strength?

Cromwell was happy to take on tasks and roles no one else wanted, which was a similar strength to Cardinal Wosley. No one wants to be weighed down in administration, but Cromwell could take on a task, and then have access to information that could serve him in the future. He could read and study and learn things that made him invaluable to the king. An early example is being given the role of overseeing the waterways, dams and ports of England. Cromwell was a lawyer; he had zero experience, just like his co-worker on the job, Sir Nicholas Carew. But Cromwell threw himself into the role anyway, and was able to pull together information and research what needed to be done, not that different to inspecting monasteries for Wolsey, or building Ipswich College and Cardinal College Oxford. He knew how to study old laws and projects so he could come up with new ideas. He did the job well enough that he was able to get King Henry interested in the ongoing work, while Carew was quietly dropped from the project.

Another strength Cromwell had came from his common background; because he had no alliances and family connections, if he wanted something one, or wanted to make changes, he could see that parliament was the conduit to power. Every time he wanted something changed, he put a Bill forward in the Commons and the Lords personally, so he had the legal backing for his ideas and changes. He didn’t leave anything unofficial, it was always documented and known by King Henry, which meant Cromwell knew he had the law on his side whenever someone argued against his decisions.

There are numerous lists of jewels in the book, which ably demonstrate how rich the world of the Tudor court was. Is there one jewel in particular that you feel was most associated with Cromwell?

The lack of a will post-1532 makes it very difficult for us to know what Cromwell wore day to day. He personally purchased a lot of gold and jewels, but he so often gave them away, so it can be hard to see what he personally valued. Diamonds often were made in gold rings and chains, but then go unmentioned ever again, so they were likely given away. Cromwell knew the jewellers of London well, one of the most popular was his neighbour in the 1520s, and so when King Henry wanted incredible collars made for the 1532 trip to Calais with Anne Boleyn, Cromwell had no trouble finding people able to handle the tasks. Cromwell handled his role in the jewel-house well it meant he was closely allied with the Exchequer and the royal mint next to the jewel-house, and allowed him to learn how to control the king’s finances, and he took over all royal accounts by 1534. Image was everything and so Cromwell needed jewels as much as anyone else, especially since he tended to prefer dark clothing, the colours of wealth and respect back in Italy. One item he took special care of was his Star of St George, given to him when he was made a special member of the Nobel Order of the Garter in 1537. He made sure to replace and upsize the diamond in that piece regularly. Cromwell is portrayed wearing a turquoise ring, but again, he owned a lot of rings of various gems and sizes, and his display likely became more elaborate over time.

Cromwell often signs his letters with the phrase “Your loving friend” which of course was convention, but who do you think really was a friend to Cromwell and why?

Chances are, if Cromwell wrote he was your loving friend, you were not his friend. He had a lot of friends, but few were nobility, as he tended to stick with the people he knew prior to arriving at court. One exception would be the noble Grey family. Cromwell worked for Thomas Grey, 2nd Marquess of Dorset and his extended family from around 1520 to 1524, and remained closely allied to them his whole life, and by association the Guildfords. Most of the families he was close with, the Gages, the Wyatts, the Parkers, the St. Legers, the Southwells, the Westons, all tended to be quiet at court. One summer Cromwell sent his son Gregory to stay with Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, but all the rest were spent with old friends away from court. He forged friendships through works with many men in the 1520s, like Thomas Boleyn, William Fitzwilliam, and Geoffrey Pole, but many of these relationships became strained in the later 1530s (though oddly, never with Boleyn). Cromwell’s closest friends were Ralph Salder, his nephew Richard Cromwell, Stephen Vaughan, Thomas Aleyn, John Creke, William Barabazon, and his sisters’ families and relatives. He also made a lot of friends while closing monasteries in the 1520s for Wolsey, and tended to stick with these low-ranked people rather than make friends at court. One exception was Eustace Chapuys, Imperial Ambassador. The pair were opposed on many issues, yet spent a lot of time together and genuinely seemed to be friends. Another good friend was Edward Seymour. The pair first met working for Wolsey but spent more time in each other’s orbit after Jane’s ascension to queen, but the pair remained close friends until Cromwell died, and not just because Gregory Cromwell married Elizabeth Seymour.

Do you think that Thomas Cromwell intended the Reformation to be so far reaching, right from the start?

It is hard to know what someone truly believes. Cromwell admittedly ignored religion until a trip to Rome in 1518, when he met the Pope and saw the abuse of the Church up close, and started reading reformist papers. Still, he was relatively quiet on religion, and Cardinal Wolsey chose not to upbraid Cromwell for his beliefs, so they cannot have been extreme (though, Wolsey was lenient to Cromwell’s ‘heretic’ friends most of the time). Most of Cromwell’s legislation to create the Church of England and appoint Anne Boleyn was around removing the abuses of the Catholic faith. It was a means to an end. Cromwell still wanted an English alliance with Catholic Emperor Charles over everything else. The problem was that the Reformation gave King Henry a lot of power and money and he liked it. European reformist leaders knew King Henry was using religion as a means of power, and respected Cromwell for trying to hold everything together. Once the king decided he wanted the money of the monasteries, the Reformation had become an unstoppable train towards a power grab over religious peace. Cromwell tried to stop the monastery dissolutions, but it was of no use, and so he oversaw the dissolution project with an eye of keep large houses open as reformist colleges. Henry got no money from that college plan and so Cromwell was regularly overruled, plus many in religious houses fought his ideas at every stage they chose dissolution and a pension over reform. In the end, the Reformation, the plans for reformed monasteries, peace treaties and alliances, and the money made from dissolution were all lost as soon as Cromwell died and King Henry sought to regain his youth by fighting France.

All of Cromwell’s reforms appear borne out of a desire to stop corruption in the Church, and the constant workload snowballed into ever-wider changes in an effort to get the Church under control. Once Cromwell was neck deep in reform, it made no sense to stop; there were so many ongoing complaints and accusations from religious houses that Cromwell probably even dreamed about them.

Was there anything in the sources you studied that surprised you about Cromwell?

One issue that continues to surprise and concern me if the issue of Walter Lord Hungerford, who coincidentally was killed the same day as Cromwell. It is well known that Hungerford’s third wife Elizabeth (nee Hussey), was kept prisoner by her husband at Farleigh Castle for four years. When this news came before Cromwell remains obscured. An argument exists that Elizabeth Hungerford managed to get a letter to Cromwell in about 1536, detailing her torture at the hands of her husband. Among the many sufferings Elizabeth went through, including starvation and poisoning, she wrote, ‘my singular good lord, I am like to perish I fear me very soon, unless your good lordship, moved with pity and compassion...’ and yet there is little evidence of Cromwell pressing the issue. I find it impossible to believe Cromwell did nothing when reading Elizabeth Hungerford’s words, given that he regularly stepped into domestic issues of ill-treated wives. The letter from Elizabeth is considered to be written in 1536 as she mentions that she has been prisoner for four years, and she married Hungerford in 1532. I believe the letter is better suited to early 1540, which is around the time Cromwell appointed William Petre and Thomas Benet to look into multiple allegations made about Hungerford, of which he was later convicted of heresy, treason and sodomy. Elizabeth Hungerford noted that the local women knew that Lord Hungerford was known to abuse his wives, though abuse of his first two wives goes unrecorded. Elizabeth’s father was executed for treason in 1537 after the Pilgrimage of Grace which would have meant Hungerford would have less reason o be kind to her, knowing her father would not come to her aid. How she smuggled a long letter to Cromwell is another mystery, but it seems totally illogical that Cromwell did nothing with this information. While Hungerford regularly wrote to Cromwell, they were not friends. Letters between them are simple instructions of work Cromwell needed done in the Heytesbury area. In Elizabeth’s undated letter, she remarked that Cromwell had previously stated that he told Lord Hungerford to just give his wife a yearly pension and leave her alone, as he had been murmuring about divorce, likely after the Hussey family was labeled traitorous in 1937. Elizabeth knew Cromwell had suggested her husband stay away from her instead of petitioning for an embarrassing divorce, and she had evidence of her attempted poisonings. She also alluded to a number of terrible things were happening at Farleigh Castle (possibly the convicted sodomy of servants William Master and Thomas Smith, though her vague words have been twisted to allude to whatever people wanted to be true over the centuries). The 1540 commission Cromwell brought against Hungerford, and the subsequent attainders have scant records, and all letters on the issue from Cromwell’s office don’t survive. Either way, Elizabeth Hungerford was freed when her husband was executed in July 1540, who by that time had gone insane (or at least pretended to in the Tower and the scaffold). I haven’t written on the topic of Cromwell and Elizabeth Hungerford in great detail, and desperately want to find the right documents to accurately date what was happening at Farleigh Castle. It is still possible the papers will surface, as a private collection of letters by Cromwell exists on the old Hungerford estates, though it would not be a surprise if the family had destroyed the most inflaming documents over the centuries.

Several images of Cromwell exist, which would you argue is the most accurate? And which is your favourite?

Cromwell researchers are lucky to have his 1532 Holbein portrait giving us an image of what Cromwell truly looked like, as well as the 1537 miniatures which are basically identical to the full portrait. The majority of figures in the period have no certain recorded portraits, many only have possible likeness, few are documented with certainty. Henry VIII had six wives and only Jane, Anna of Cleves, and Kateryn Parr have certain likenesses. Cromwell’s portrait is well known; it is on every book cover on the topic, and I had to work to get even a slightly different look for my 2025 book cover, otherwise all books on the man start blending together, since any likeness is a copy of the 1532 painting that Ralph Sadler saved from destruction. Anything created with Cromwell’s image after 1532 draws from this one image, with an expression added by the individual artist, but we always come back to the Holbein image. There has been plenty of criticism of Cromwell’s 1532 portrait, and it is true it is not one of Holbein’s masterpieces. From my personal point of view, the portrait is loaded with specific humility, just as Cromwell must have requested. The most striking detail is that the portrait is done almost in profile, rather than in the more expressive three-quarter pose Holbein used with most subjects. This shows several key things about Cromwell. The profile portrait had been popular in Florentine art, constantly used in portraiture to an excellent degree of beauty. The profile style had been popular as it represented the ancient style of portraits that had been used on coins before portraits lost favour for almost a millennium. By Cromwell choosing profile over a more revealing pose, he appears more a symbol than a man. The private man with an adventurous and obscure past reveals almost nothing about himself. The portrait does not have one central focus; Cromwell’s face is not centred, nor his body, and he is set deep in the frame, almost untouchable or unreachable, a man keeping the world at arms-length. He sits in a rigid pose, a suggestion of substance and steadfastness, and Cromwell’s eyes, up close a golden brown, are concentrated on an unknown focal point. His mouth offers absolutely nothing; his lips offer no emotion, though his face gives the impression of gritted teeth, his eyebrows likewise give no hint to Cromwell’s feeling at the time of painting, though one sits a tiny fraction higher than the other as if his mind is on something specific. Cromwell’s choice of clothing offers no indication of his personality. Cromwell had a fine collection of clothes in various fabrics, yet he wore a featureless black velvet gown with brown fox fur. A glimpse under his gown offers nothing but black, likewise a plain black soft cap over dark hair, long enough to cover his ears and down into the back collar of his gown. Black was a symbol of wealth, certainly among Florentine merchants, plus wearing black showed no hint of allegiance. A simple portrait for a busy man, showing self-discipline with no outward idolatry. Cromwell has a paper in his left hand showing he is a lawyer, and his forefinger wears the heart-shaped turquoise ring listed in the Austin Friars 1527 inventory. The portrait shows a capable, skillful, observant man, and his merchant, legal and religious personality laid out on the table before him, and almost exactly in the style of Sir Henry Wyatt’s portrait, right down to the paper between his fingers. While the portrait lacks the detailing of Holbein’s works, Cromwell must not have felt the need to have it softened in any way, unlike many other sitters like Thomas More. Cromwell perhaps had confidence in his outward appearance as he quietly continued to slip through the royal court. The portrait has been used by historians to describe Cromwell as a simple or cruel man, and reports of him walking with an ‘awkward gait’ or ‘plodding walk’ do not have any contemporary sources. Cromwell was in his late-forties by this time, and easily could have walked with an injury or limp after an exciting life, but the suggestions seemed to be rooted in periods where Cromwell was sporting a temporary injury, including one when he came off his horse. In correspondence, Cromwell’s image is almost never mentioned, not his height, expressions, tone of voice, nothing. Cromwell is similar to Anne Boleyn in this way, as she has no definitive image left behind, and any recorded descriptions lack credible authors. Both she and Cromwell largely exist how we want them to exist.

What do you think was Cromwell’s greatest weakness?

Cromwell liked to give people second chances, likely because he had been given them himself in the past. He would see people in need and take them in, or give people jobs, make their children his wards, or give people chances to repent misdoings of many kinds. Obviously none of us will ever have access to the information Cromwell had when making these decisions, but there are definitely people I would have personally not forgiven, had I been in his shoes. Several people were able to operate in Cromwell’s blind spot as a result, one being Dr Thomas Legh, one of Cromwell’s chief monastery inspectors, who was accused of violence and corruption during monastery visitations in 1535, as stated by those he hurt, and those in his own party who witnessed his behaviour. Legh wrote to Cromwell after one accusation, saying, ‘it would be folly in me to excuse myself if my actions did not correspond; and though a man is given to sensual appetites, I am not addicted to such notable sensualities and abuses as you are informed.’ A letter from another inspectors had alluded to Legh not giving nuns ‘their rights’ prior to this accusation, and while Cromwell moved Legh away from to other locations, it baffles me the same way it baffles me that Catholic priests are simply moved away from their victims towards new victims today. Regardless of good works done in the past, Legh needed to be shut away in my opinion. He was a cousin of Bishop Rowland Lee, one of Cromwell’s longtime friends, who also had a reputation for cruelty in the Welsh marshes. I’m honestly not sure I would want to hear Cromwell’s justification of these long assistance associations, but Cromwell trusted Bishop Lee with everything, including with Gregory Cromwell for many summers in the 1530s. Plus, once out of Lee’s sight, Gregory Cromwell went on to commit some of these same crimes himself, which Cromwell then had to handle and cover up.

What is the one thing that you would like our readers to take away about Thomas Cromwell having read your book?

The book is for people who like to dig down into the details of what was happening in the 1520s and 1530s. You can’t get the whole sense of a person from their admin work, but it allows readers to connect dots between people, see who was writing to who, about what, and what they were doing day to day without having to digs through everyone’s mail. It helps to see where tales and myths arose, and what was really said, rather than the misinterpreted stories that seem to persist. Thomas Cromwell as a person is better seen in the letters he received than just the ones he wrote, so I tried to give as much context as possible about what was in Cromwell’s inbox rather than just his outbox, but there came a time when Cromwell was so overloaded with mail that only some stories can stand out. Sometimes Cromwell’s rambling can be a hard read, and I tried to add 21st century punctuation to his letters so they are not as difficult to understand as they are in his own handwritings. The sheer range of issues Cromwell dealt with is on display in his letters, and you can see that while England was undergoing vast change, it was because a man was sitting in an office somewhere, likely with ink-covered hands. Because of what I learned in his letters, I was able to write three fiction works, and then The Private Life of Thomas Cromwell, which fills in the gaps of his life, and Planning the Murder of Anne Boleyn, where tracking correspondence shows how he had to plan an intentionally haphazard case around an innocent woman. This book of letters is my reference point for all the work I do on Cromwell; I can search the book for a name, as connect dots I need to working on any topic.

Are you working on anything at the moment, and if so can you tell us anything about your current research?

I have two manuscripts open at the moment, one on Sir Ralph Sadler, Cromwell’s adopted son, which is non-fiction. Sadler learned the hard way that rising high under your monarch was not a good idea, and was able to fly under the radar and still have a 50-year court career. The other book, which will be released in 2026, is Becoming Thomas Cromwell, which is the first novel based on Cromwell’s life in Florence from 1503-1513. The book is about the Frescobaldi family’s smuggling operations for King Henry VII and young Cromwell’s friendship with neighbour Machiavelli. Because the whole period is something of a mystery, I have a wide range of options for the storylines.

Thank you so much to Caroline for such a fascinating Q&A, we hope you enjoyed it as much as we did. Anyone else really excited for Caroline’s next books???