Mary Tudor, Queen of France, was laid to rest on 23 July 1533. She had died at Westhorpe on 26 June and afterwards she lay in state in the chapel there with candles burning and a divine service sung daily until her funeral.

The mourners arrived at Westhorpe on 20 July, ahead of the final requiem mass taking place the following day. The mourners were led into the chapel for the requiem mass by chief mourner, Frances Grey who was flanked by her younger brother Henry, earl of Lincoln, and her husband, Henry Grey, Marquess of Dorset. Behind her followed the rest of the mourners in pairs. Eleanor, Mary’s daughter Countess of Cumberland, was accompanied by Katherine Willoughby (who would soon become her step-mother), Anne and Mary Brandon followed next, each with their husbands, then further ladies and her household. As per the custom, Charles Brandon did not attend his wife’s funeral. In addition to the funeral, Henry VIII ordered masses to be held in Westminster and St Paul’s for his beloved sister so it is possible Brandon attended one of those, comforted by his best friend. In honour of her position as the dowager queen of France, France sent a herald to pay their respects and assist with the ceremonials.

On 22 July, six gentlemen carried Mary’s coffin to a waiting carriage. The carriage was draped in black velvet with a flag bearing Mary’s arms on each corner. It was to be drawn by six horses who were also dressed in black velvet embroidered with Mary’s arms. Two ushers, bareheaded and kneeling awaited the coffin which, as it reached the carriage, was draped in a pall of black cloth with cloth of gold embroidery of a representation of Mary wearing her crown and state robes, holding a sceptre

The procession left Westhorpe, led by one hundred poor men, dressed in black hooded gowns, each carrying a taper. Behind the men walked the clergy of the chapel at Westhorpe carrying a cross. Mary’s chamberlain, Lord Powys, and Clarencieux, Garter Kings of Arms, rode behind on horses trapped in black, followed by the nobility ahead of the carriage bearing her coffin, which was surrounded by one hundred torches burning brightly.

Directly behind the carriage rode Frances, with her husband and brother-in-law, Lord Clifford either side of her. Ten ladies rode behind Frances, each with a page and two funeral mourning chariots behind them. Finally, Mary’s servants and the remainder of her household walked at the rear of the procession, whilst anyone else wishing to join the procession and pay their respects followed.

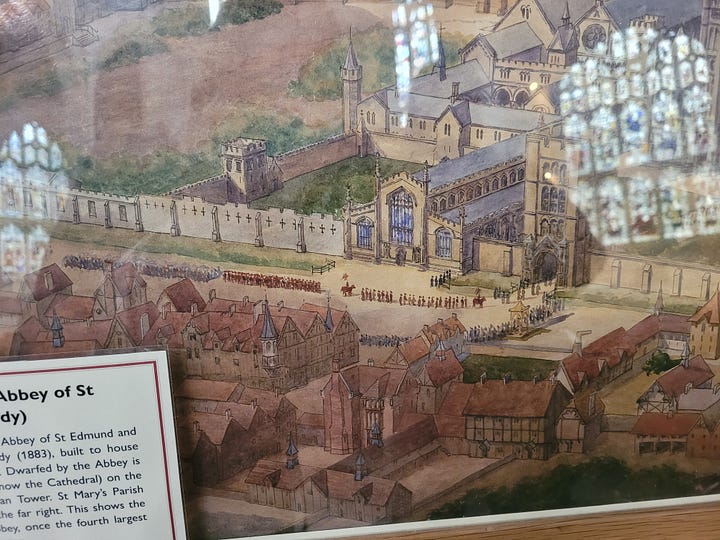

Along the route various parishes had their chance to pay respects and offer tribute to the beloved Tudor princess, each parish being given money to offset the costs of their tribute. The procession was heading to the Abbey of St Edmund, where it arrived around 2:00pm. It was met there by the clergy and it then continued to the first gate where Abbot Reeve and the monks of the abbey joined the procession. At the second gate the coffin was moved from the carriage to a hearse for the final part of the journey. One hundred torch bearers surrounded the hearse which was covered in a cloth of black sarcenet with gold fringes and bore Mary’s arms and motto ‘La Volonté de Dieu me Suffit’ (God’s will is enough for me), embroidered in gold. The bishop of London joined the procession and accompanied the coffin on the final leg of its journey into the abbey church. The route was lined in black and escutcheons of Mary’s arms.

Once the procession had entered the abbey and filed into their places, the clergy chanted a dirge and the French herald declared ‘Pray for the soul of the right high excellent princess, and right Christian Queen, Mary, late French queen, and all Christian souls’. The mourners were then welcomed into a large chamber where food was provided and lodgings for those who stayed overnight. Some of the mourners remained with the coffin throughout the night in vigil.

The following morning two masses were heard before breakfast, then the procession was led to the church for a requiem mass. Mary’s daughters and Katherine Willoughby as a ward of Charles Brandon, were all given the opportunity to approach the coffin and make an offering of palls of cloth of gold which they handed to the Garter king for him to lay over the coffin. The offerings were followed by a sermon to conclude the service. The melancholy rites were then completed but Mary’s daughters were not present at this point. They had instead returned to another chamber in the abbey. This was not usual protocol but it is unclear why the ladies did not remain for the rites, possibly they were overwhelmed with grief at the finality of events.

Mary’s coffin was then carried and lowered into her grave. Her household officers then broke their staves of office, and dropped them into the grave; the broken staffs signifying the end of their service to their mistress, thus concluding the funeral of Mary Tudor, Queen of France.

The abbey invited the residents to partake in food in locations around the town and received a small gift of money. The one hundred poor men who had led the procession were included in this invitation and also retained their black gowns which had been paid for on their behalf. The torch bearers, heralds, and officers also received money for their expenses.

Sadly, this was not the final resting place for Mary. The abbey was subject to the dissolution of the monasteries though Henry did order that Mary’s remains to be moved before the abbey was destroyed. In 1539 Mary was therefore moved and reinterred in St Mary’s Church, Bury St Edmunds. Abbot Reeve, who oversaw Mary’s funeral service died only a few months after the dissolution of the abbey, and he is also buried in St Mary’s.

Sadly, this was also not the last time Mary would be disturbed. In 1784, Mary’s grave on the north side of the sanctuary was meddled with and her coffin was opened and locks of her hair were taken. Mary was once more reburied in the same place and a stone placed atop with the engraving ‘Mary, Queen of France 1533’.

Having already been disturbed twice, Mary was yet again disturbed a few years later during preparations in the church to pave the chancel in marble. On this occasion it was thought that Mary’s grave was a cenotaph but when discovering that it was in fact her actual grave it was left alone and the tombstone replaced.

In more recent years the Mary Tudor window, a gift to Queen Victoria in 1881, has been installed, beautifully depicting Mary’s story.

A white marble kerb was also added to her tomb following a visit by Edward VIII in 1907. It may appear that Mary’s grave is underwhelming considering her status but she lies in a beautiful, peaceful, church.

As for the locks of hair that were taken, one can be seen in the Moyse’s Hall Museum, Bury St Edmunds, having previously been in the possession of the family of Reverend Ashby. Another is kept at Knowsley Hall, having been taken by Horace Walpole.

Mary led an eventful life, if you would like to know more about her, my book, Mary Tudor, Queen of France, is available in the usual places.

I love this post. I want to read more about this Mary Tudor. She seems like such a vibrant person.

RIP to a Tudor Princess. Thanks for giving us an opportunity to relive this historic occasion. Also, looking at the small description next to the artifact of Mary Tudor's hair. Badass move marrying the man she wanted in secret and being able to stand by her decision despite her brother being the King of England and known for his temper.