As it neared midnight on 12 July 1536, a man spoke his last words ‘Lieber Gott’ (Dear God), he did not have a priest with him for a last confession, but was instead in the company of some of his closest friends in his chamber in Basel.

His name was Desiderius Erasmus, arguably the best scholar of his age. He lived through one of the most religiously turbulent periods in history and left behind a wealth of literature. He had survived most of his friends, including Thomas More who had died only the previous year, devastating Erasmus, who wrote:

What has happened in England to Fisher and More, a pair of men, than whom England never had a better or a holier, you will learn from the fragment of a letter which I send you. In More I seem myself to have perished, so completely was there, as Pythagoras has it, but one soul to both of us. Such are the tides of human life!

Erasmus heard the news about his friend on his return to Basel in August 1535. He had returned to to supervise the printing of Ecclesiastes, Sive de Ratione Concionandi (Ecclesiastes, or On the Art of Preaching). On arrival he was welcomed in to the home of Hieronymus Froben, the son of his former printer and dear friend Johann Froben.

Having suffered with frequent bouts of illness over the past few years Erasmus knew well he was not long for the world and would soon be joining his friends and former pupils. He spent much time in his chambers but by spring of 1536 his health was deteriorating and he kept to his chambers entirely.

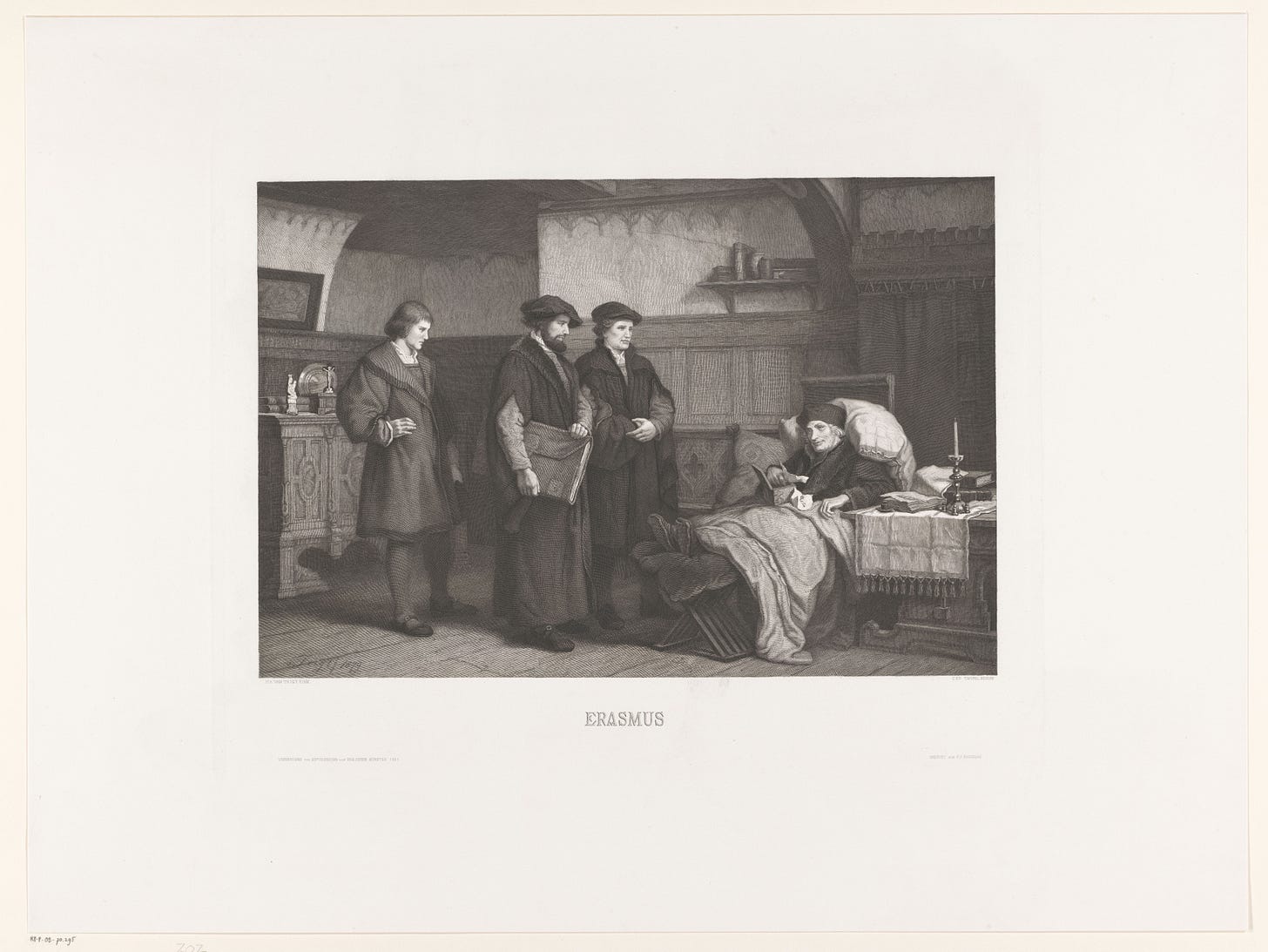

Erasmus had kept working almost to the end, but on 12 July his closest friends including Hieronymus and his godson, Bonifacius Amerbach gathered at his bedside and remained with him until the scholar took his last breath. For someone so pious it may seem strange that he did not call for a priest to hear his last confession, but Erasmus had spent much of his life writing about religion and reform of the Catholic Church. He did not believe a priest was needed to absolve one of their sins at the point of death.

Another friend, Beatus Rhenanus, was not present at his death but would later publish Erasmus’ Collected Works and within the dedication to Charles V wrote his friends life story. Writing about his death, he stated:

The arthritis, with which he had been afflicted at Freiburg, so confined him to his bed until nearly the following autumn that he rarely left his chamber, and only once was he outside of his room. And yet in such torturing of his limbs he never ceased to write whenever he felt the least respite, as is proved by his little commentary On the Purity of the Christian Church, and this present revision of Origen. But his powers diminishing little by little, for he had suffered almost a month with dysentery, he at length perceived that his end was near; and so, surrounded as ever by those visible and eminent testimonies to his Christian patience and his devout mind by which he witnessed that he had fixed his hope on Christ, crying out constantly, ‘Mercy, O Jesus, Lord deliver me, Lord make an end, Lord have mercy on me,’ and in the German language, ‘Lieber Gott,’ that is ‘Dear God,’ on the twelfth of July near midnight, he died.

Following his death many town officials and scholars came to pay their respects to the scholar. News spread of his death and on the day of his funeral crowds gathered to watch the procession which was brimming with officials, scholars, and friends, some of whom carried him on their shoulders to Basel Cathedral (now known as Basel Minster). He was buried near the altar where his tomb can still be seen today.

Erasmus may have lived much of his life in poverty but he died a wealthy man, leaving behind bequests of books, plate, and money. He named Hieronymus Froben, and Nicolaus Episcopius as his executors and his godson Bonifacius Amerbach as the heir to all of his estates remaining following the additional bequests, which included money that his executors were to distribute for the use of the poor, the aged and the infirm, also to provide dowries for young women in hardship wishing to marry, then among the youths in hope of good scholarship: in short, whomsoever they judge worthy of relief.

The scholar may have gone but his work lived on. Those wishing to honour him tried to accumulate all of his works to publish them together but some had already been lost. Bonifacius sought a portrait of his godfather from the Hans Holbein, the artist having retained one for himself after the pair had become good friends.

Erasmus once wrote ‘I write what will live for ever’ and he was certainly correct about that.

I hope you have enjoyed this post, if you would like to know more about this incredible man, my book, Desiderius Erasmus, The Folly or Far Sightedness of Renaissance Europe's Greatest Mind is due to be published early in 2026 and is currently available for preorder in the usual places, if you are outside the UK it is available for preorder from Blackwells and includes delivery to many countries.

Thank you! I'd like to read some of Erasmus' writing. What is a good place to start?